Mule Canyon

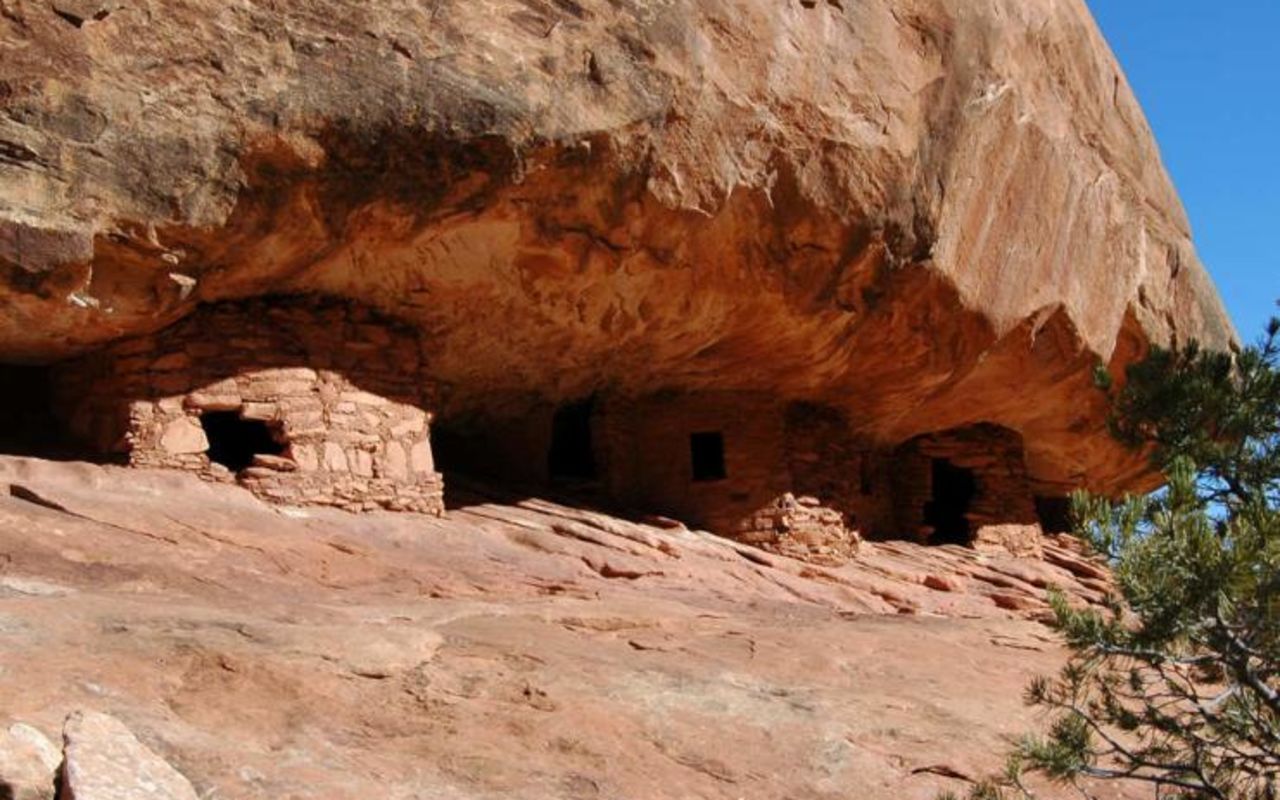

Mule Canyon Ruin is a small Ancestral Pueblo village (formerly referred to as Anasazi), used for living quarters and religious ceremonies. The masonry structures now visible were constructed of sandstone blocks set in wet soil mortar. The construction materials were obtained from the immediate vicinity of the site. During occupation, the walls of the structures (except, the kiva) were higher, and all were roofed. The roofs consisted of a log frame, covered with progressively smaller limbs and sticks, then sealed with soil mortar. The floors of all the structures consisted of hard-packed soil.

The structures include a 12 room "room block", a tower and a kiva. The room block was constructed primarily for sleeping, storage, and shelter during inclement weather. Most, if not all, of the daily chores and activities of the Ancestral Puebloans were carried on out of doors. The kiva was used primarily for religious ceremonies, and may also have served as a community meeting place and work area during bad weather. The tower's function is unknown, though it may have served in a religious, observatory and/or communications capacity. These structures were occupied during the 11th and 12th centuries A.D.

Unique features of the site are the tunnels (now sealed) which connect the kiva to both the room block and the tower. Tunnels are rarely found in Ancestral Pueblo sites, particularly in the vicinity of Mule Canyon Ruin. Aside from providing an enclosed passageway from structure to structure, the specific purpose of the tunnels is unknown.

The masonry structures which are now visible represent the last occupation of the site. These structures were built atop the remains of an earlier Ancestral Pueblo occupation, which took place during the 9th and 10th centuries A.D. The structures which were built during this earlier occupation included a pithouse and rare earthen kiva. The earthen kiva is similar in appearance and function to the masonry kiva. However, except for its roof, this kiva was constructed entirely of earth. Both of these structure have been covered with soil to protect them from weathering and deterioration.

Stabilization

After the abandonment of the site, the roofs and missing wall sections of the masonry structures were destroyed by weathering. Eventually, wind blown sediments covered the ruin, protecting it from further deterioration. After the site was excavated, it was again exposed to the elements. To arrest the deterioration by wind and water, all of the masonry structures were stabilized.

Stabilization primarily involves replacing loose and crumbling mortar and wall sections essential to the stability of a structure. Care is taken to match the original color, form and texture when repairing with modern materials. Often, room interiors and the surrounding terrain are regraded to aid in draining water away from the walls and structures. The focus of all stabilization activities is the safety of the visitors and preservation of the structures. It is not intended to reconstruct the site to its original appearance. Therefore, much of what you see at the site appears as it did when unearthed by archaeologists.

The People

The Ancestral Pueblo are the prehistoric Indians who inhabited the Four Corners Area from approximately 1 to 1300 A.D. You may have heard the Ancestral Pueblo referred to as the Anasazi. Because "Anasazi" is a word that comes from the Navajo tribe and roughly translates to "ancient enemy," modern descendants of the tribe have made a push to move towards "Ancestral Pueblo" instead.

The Ancestral Pueblo had no formal system of writing, and therefore left no written record of their culture or appearance. What we know today about the Ancestral Pueblo is derived from archaeological research. Much of the information was gathered through the excavation of sites such as Mule Canyon Ruin, and by studying the modern day Pueblo Indians of the Southwest. Archaeologist now generally agree that the modern day Hopi Indians of northeastern Arizona and the Zia, Sandia, Jemez, Taos, and Zuni Indians of north central New Mexico are at least partially descendants of the Ancestral Pueblo.

From skeletal analysis and comparison, it is surmised that the Ancestral Pueblo were similar in appearance to the modern Pueblo Indians. The Ancestral Pueblo were short by today's standards; the men averaged about five feet, four inches tall (somewhere over six feet tall), and the women averaged about five feet tall. Their skin was dark brown, hair was black, and they probably had brown eyes. Though small in height, they were most likely a very strong and sturdy people.

Ancestral Pueblo clothing was simple and functional. Most items were woven of plant fibers, and some were made from animal hides. In summer, the women wore only an apron and the men only a breechcloth. Both wore sandals to protect their feet. These items were usually fashioned from woven plant fibers. In winter, the Ancestral Puebloans wore robes made of animals hides or feathers from the turkeys they raised. Other clothing included belts, sashes, calf-length socks, jackets and blankets. Cotton was introduced to the Ancestral Puebloans around 750 A.D. by tribes to the south, and from this they began weaving many of their cloth items.

The Ancestral Pueblo also wore simply jewelry. Necklaces and pendants were fashioned from polished bone and rock, and suspended with leather or plant fiber cord. Sea shells were also used in jewelry, traded from as far away as the Pacific Coast.

For food, the people of Mule Canyon Ruin raised corn, beans and squash on the surrounding mesa top. They also collected a variety of wild plants, nuts, bulbs, and berries. Meat from their wild turkeys as well as wild game supplemented their diet. The men hunted deer and bighorn sheep with a bow and arrow, or snared and netted rabbits and other small game. Varying combinations of these items were included into a stew, constantly simmering over the family hearth.

To cook, eat, store and carry their food and other items, the women of Mule Canyon Ruin made a wide variety of fine pottery. It is assumed that Ancestral Pueblo women were the potters, as women in the modern Pueblos are. The pottery was made by coiling the clay into small "ropes". These ropes were laid one atop another to achieve the basic form of the vessel, then pinched together, smoothed and polished with a stone. Organic or mineral pigments were applied to the surface, often in lavish geometric designs. The piece was then "fired" or baked. Ancestral Pueblo pottery consisted of bowls, dippers, pitchers, mugs and cooking and storage containers of various shapes and sizes. Most of the pottery produced at Mule Canyon Ruin exhibited black and white designs. However, some red and orange pottery was also produced and/or traded from northern Arizona.

The excavation of Mule Canyon Ruin yielded a variety of stone and bone tools used by the Ancestral Puebloans to aid in their daily chores. These included chipped and flaked tools such as knives, scrapers, saws, drills and arrow points. Hammers, axes and mauls were also discovered, produced by grinding the stone into shape. Bone tolls included scrapers, awls and weaving tools such as needles.

The Ancestral Pueblo of Mule Canyon Ruin suffered many ailments, diseases, and injuries brought on by their diet, living conditions and difficult way of life. They suffered from malnutrition and osteoporosis, caused by a low-protein, high-carbohydrate diet. Gum and tooth disorders were complicated by chewing the sand that became mixed with their food. Respiratory infections and tuberculosis were common, brought on by breathing the smoke of enclosed fires and by parasites. They particularly suffered from degenerative arthritis, caused by lifting and carrying heavy loads, and irritated by sleeping in cold, damp rooms.

The Ancestral Pueblo had a high infant mortality rate. If one survived childhood, they could expect to live into their early forties (some lived into their eighties). When an Ancestral Puebloan died, they were buried in a shallow grave, usually in the refuse area. Often, a few special items such as pottery, tools, weapons or basketry were buried with the deceased, presumably to carry into the afterlife. One such burial was unearthed during the excavation of this ruin.

Administration

Mule Canyon Ruin is administered by the Bureau of Land Management, U.S. Department of Interior. For more information about this or other archaeological sites in the area, please contact the Bureau of Land Management offices.

Please do your part to help preserve this and all other public resources. Report any acts of vandalism or damage to the Bureau of land Management or local authorities.

Monument Valley Weather

Average Temperature

Average Precipitation

Average Snowfall

Articles

View AllHappy Trails in Piute County

What do Delano Peak, the Paiute ATV trail and Butch Cassidy all have in common? Utah’s Piute County,...

8 Secrets to Sustainable Travel in Park City

Want a big adventure to Park City without a big environmental footprint? Utah.com can help you explo...

Utah County Is Festive As Heck

Fireworks, parades and corn on the cob — oh my! Utah.com has the scoop on the best festivals and fai...

Natural Bridges National Monument: A Hidden Gem, Not a Second Fiddle

An under the radar destination that should be on your radar. Learn all about Natural Bridges, Utah a...

Plan a Guys Getaway in Vernal

Planning a guys trip? Why not hit the ATV trails in Vernal, Utah with your crew? With all kinds of w...

Treat Yourself to a (San Rafael) Swell Winter

The San Rafael Swell is one of Utah’s hidden gems, and it gets even more hidden in the winter. Utah....

Plan a Triathlon of Fun in Greater Zion

Looking for things to do in St. George this fall? In addition to the IRONMAN 70.3 World Championship...

Color Me (Insert Emotion Here): Where to See Cedar City’s Feel-Good Fall Foliage

Richly hued views await you in southern Utah this autumn. Peep the changing leaves on a scenic drive...

Play Outside and See a Play Outside in Cedar City

Take a visit to Cedar City, Utah, and see why its access to both world class theater and stunning ou...

Mapping Out Utah’s Tastiest Cuisine

Getting to know the Beehive State means experiencing its sites and unique flavors. Discover both whe...

Get Your Peach Thrills in Box Elder County

Utah’s Box Elder county is a peachy paradise — part mountain range, part desert, part orchard and al...

9 Highest Peaks Across Utah

Take a peek at the tallest peaks in Utah. From Kings Peak to the Deep Creeks, Utah.com gets to the t...

Paving the Way for Everyone: All-Access Trails in Utah

From a wheelchair accessible waterfall trail to a lakeside boardwalk laden with wildflowers, these U...

Local Legends in Utah

Ever been curious about urban legends in Utah? Utah.com fills you in all things folklore with our gu...